Language learning has never been easier for the people of the world.

With the amount of media available from each individual country, the interconnectivity of the world’s people, and the rise of the internet, there is now more information available on language learning than there has ever been.

Yet, that does not mean that language learning is easy. It requires hours of work and study, hundreds for the languages closest to your own and thousands for those languages far removed.

Learning a language required you to master speech, listening, speaking, and writing.

While learning the speech, listening, speaking properly can make you feel confident in your language skills, learning the writing can make or break a potential language learner.

For the lucky ones, the alphabet is the same alphabet as the languages you know already, like English and French.

For the unlucky ones, it is completely different, like Russian and Georgian. However, for the most unlucky of language learners, there is more than one alphabet to learn.

Then there is Japanese. Japanese has 3 regular alphabets and 1 infrequently used one. Why does Japanese have 3 alphabets?

Today, we are going to explore Japanese’s 2 alphabets and examine why this language would have more than one.

Kanji

Kanji is the oldest of the Japanese alphabets used, and actually comes from ancient China.

While the characters of this ancient Chinese script appeared in the 1st century AD, they probably weren’t properly introduced or comprehended until at least the 5th century AD.

We think this due to the appearance of many objects imported from China in Japan through these centuries, but no written texts appear from Japan until the 7th century AD, and we only have fragmentary evidence of diplomatic missions to Korea and China beginning in the 5th century AD.

These characters were probably introduced by the kingdoms of Korea, when they were trying to establish diplomatic and trade ties to the Japanese islands and the Yamato people.

For all intents and purposes, Kanji are logo graphic characters that represent a word, morpheme, concept, or idea. Most of these characters are unique, but have similarities that represent a grouping in the language.

For example, fish is represented by the character ‘魚’and pronounced ‘sakana’.

If you look at most kanji for fish names in Japanese, they will have the ‘sakana’ character in the kanji, a good example is Tuna which in Japanese is represented by the character ‘鮪’ and pronounced ‘maguro’.

As you can see, the sakana symbol is on the left of the Kanji. There are well over 50,000 unique Kanji in Japanese and to become fluent, you need to be able to read at least 10,000 due to the amount of words each one designates.

Hiragana

Although ancient Kanji symbols worked well enough at the time, there were a couple of big problems that both the Korean and Japanese languages experienced with the writing system.

Those issues were that Kanji wasn’t created for their languages, and it was really difficult to learn.

If you have an independent language that uses a borrowed writing system, that system may not capture the nature of the language perfectly.

Any unique tones or pronunciations or subtle changes in speech in words may be lost.

This can be seen heavily in the adaptation of the Latin alphabet for the Celtic languages and the Arabic alphabet for the West African languages.

They were adapted in strange combinations that didn’t capture the essence of the languages well. This too happened with Kanji and Japanese.

Kanji just didn’t capture the essence of Japanese phonetics or grammar in its bold logographs.

So, a separate writing system was developed to accommodate for Japanese grammar that was called originally ‘Man’yōgana’ and nowadays is called ‘Hiragana’.

While at first, elitists and court officials disliked hiragana, its popularity amongst the common folk and women – who at the time were not amongst the people at court – made it one of the most abundantly written scripts and in today’s world you simply can’t write Japanese without it.

Hiragana literally means ‘simple kana’ and it is easy to see why. It is mostly used to form the core of grammar in a sentence without actually signifying an object.

This means it is used for particles and postpositions that mark sentence subjects or objects or serve the same purpose as prepositions – like ‘to’ and ‘from’.

Japanese is also an agglutinative language that uses suffixes on words to denote intent and meaning. For instance, ‘watashi wa taberu’ means ‘I eat’ with ‘taberu’ being the verb ‘to eat’.

However, by adding the suffix ‘-tai’ we change the meaning, as ‘-tai’ on the end of a verb denotes ‘want’ along with the verb’s actions.

So, ‘watashi wa tabetai’ means ‘I want to eat’ and the ‘-tai’ part of the verb would be written in hiragana while the rest would be written in Kanji. Hiragana is used for almost all grammatical suffixes and changes in a Japanese sentence

Since hiragana is written for Japanese, it is used to explain Kanji as well. You will often see Kanji with a small amount of hiragana written to the right-hand side.

This is because Hiragana has a sounding system, each letter has a specific sound that when combined creates words – very much like the English alphabet.

This really helped teach and explain Kanji back in the day and continues to be used for this purpose as well.

Katakana

Katakana is the third major alphabet of Japanese, though it is not used as heavily as Kanji and Hiragana. It was developed in the 9th century after Hiragana as a form of shorthand by Buddhist monks in Nara.

Though it came from humble origins, this shorthand proved popular, especially with officials as writing Kanji can be long and laborious, as well as difficult to remember what Kanji is for what concept.

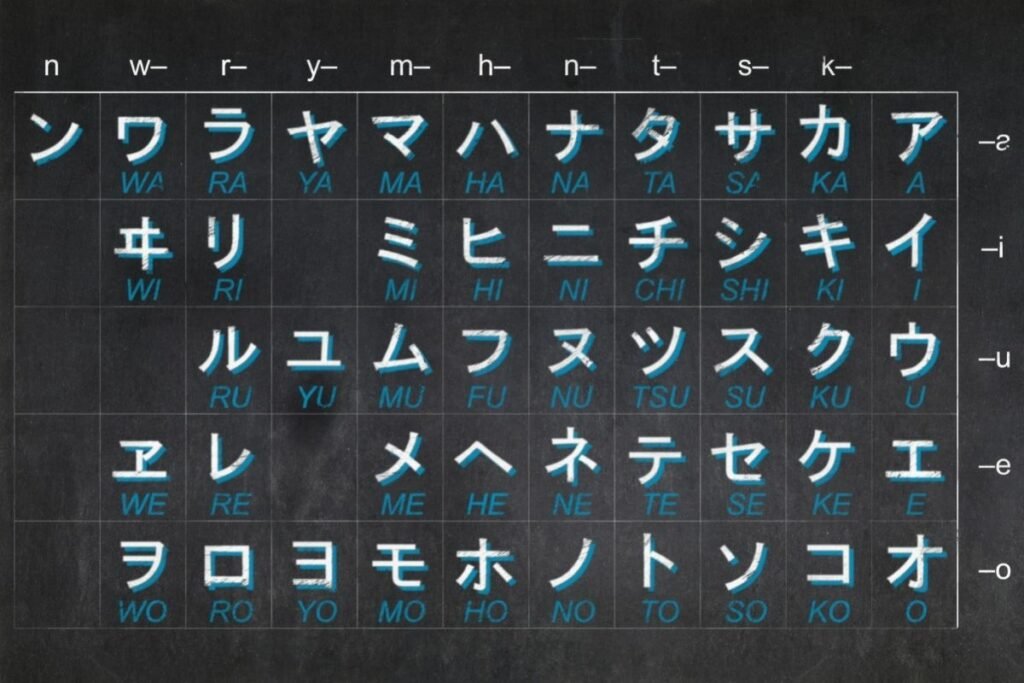

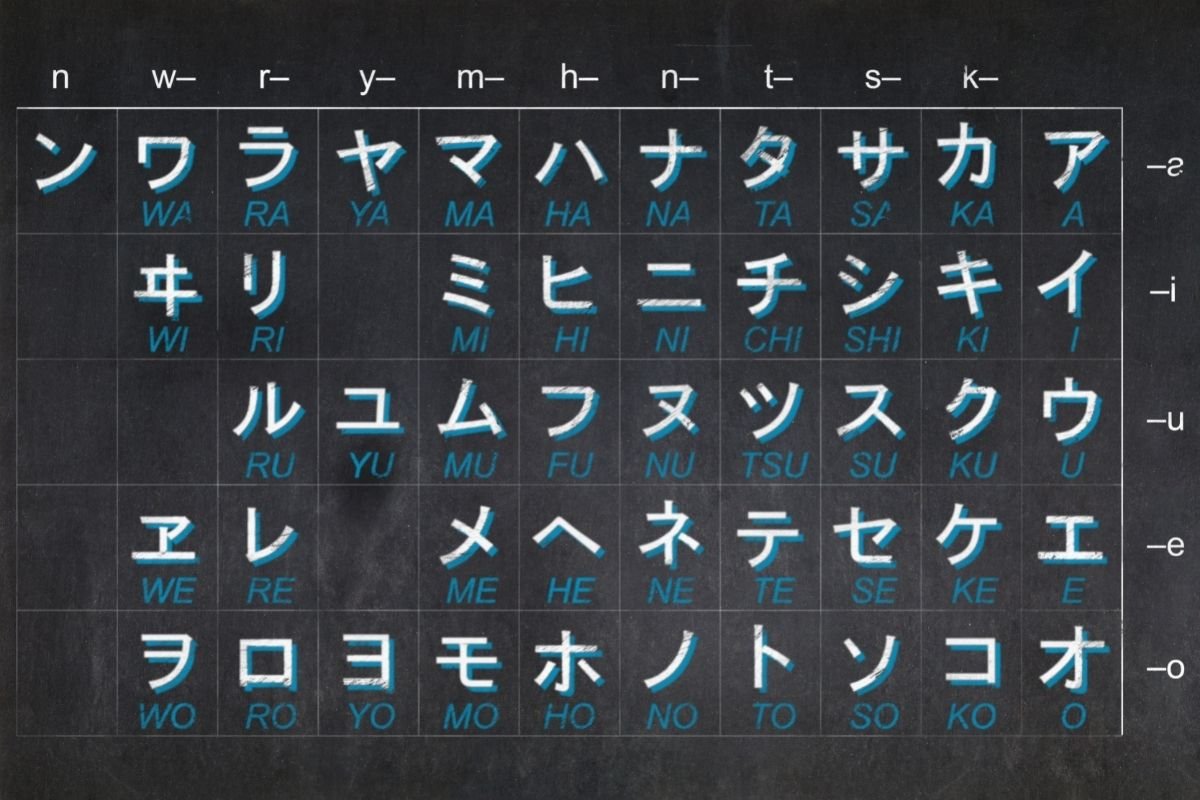

Like Hiragana, Katakana uses a sound system and basically mirrors Hiragana for all 48 sounds of that alphabet (see also ‘What Is the Difference Between Hiragana and Katakana?‘).

However, while Hiragana was made an integral – and necessary – part of Japanese writing through grammar, Katakana did so for essentially anything that was not already categorized by Kanji.

This may not seem like a lot, but over the 1000 years of its use this has come to symbolize things that are from foreign things before they have become naturalized into Japanese society.

For example, let’s take two words. London or in Japanese ‘Rondon’ (ロンドン) and tobacco or in Japanese ‘tabako’ (たばこ).

London is a relatively new term of only a 100 or so years of use in Japanese, and it is a city in a foreign country, so in Japanese it has been tweaked to fit the Japanese sounds in the language and then written in Katakana to symbolize its foreign nature.

However, tobacco has been around in Japanese culture for a little longer and its use in the language is much more regular.

As such, over time the sounds have been naturalized into a Japanese sounding word and it is so common, it is now written in Hiragana.

Katakana is not only used for foreign objects, though. It is used to denote onomatopoeia (like ribbit-ribbit) and also for scientific words for objects, minerals, and animals in much the same way we have Latin names for these things, for instance the word for cat in Japanese is ‘Neko’ and it is written in Katakana.

Romaji

Romaji is technically the fourth Japanese alphabet, but realistically it isn’t and is used more for westerners’ benefit than anything.

For you see, Romaji is just our standard Latin alphabet, and it is used to portray foreign names, acronyms, phrases, and commercial products.

This is due to the lack of any alphabet like the Japanese ones outside of Japan, which can be a problem for Japanese people traveling (see also ‘Do Japanese People Have Middle Names?‘).

As such, Japanese passports will have Romaji on them, as it is the most prevalent alphabet in the world and will be understood or at least recognized in almost all countries.

In order to expand international business and relations, this alphabet was adopted, but it is only used in very specific circumstances and not every day.

Final Thoughts

Many Japanese language learners tear their hair out at the thought of having to learn 2 tough alphabets and then 1 insanely difficult one, but purely from the perspective of a linguistics lover, I think it’s wonderful that Japan has 3 alphabets.

It really shows the vibrancy and historical nature that underpins the Japanese language and makes it all the more beautiful.

- What Is a Maiko? - July 13, 2025

- What Does Domo Arigato Mean? - July 12, 2025

- What Does Naruto Mean? - July 12, 2025